Hacking Video Games: A Software Engineering Approach

We’re going to be doing a brief discussion on an approach to attacking client-side video games. I am going to make several assumptions about our reader: you’re experienced with binary (and hexadecimal), you understand basic computer science skills (can program and understand hash-tables and computational organization), and you hate losing games.

Understanding File Parsing

When video games first came out, this topic would be trivial. We would simply do a quick look to figure out where are save files are stored on our operating system, and then we would just modify the values in that file. Often times, XML or INI would be used to store the information. This wasn’t a big deal for developers because we often did not have to share the information with servers or vast networks like we do now, so there is no reason to secure the information. As the first online games were introduced, so too was the ability to manipulate the online content, and then security was put in place to prevent this: checksums, custom serialization, endianness, custom primitive storage, etc. This article will be talking primarily about client-side attacks to a video game, pertaining chiefly to custom, developer made save-files.

Top Down Approach

Let’s take a look at an example before we continue. A popular client side game we’ve all loved at one time or another is Skyrim. Generally the tools I use are restricted to a hex editor and some arbitrary language IDE open on the side to implement as I go. For Linux the hex editor I recommend is Bless and for Windows definitely use HxD. For this example I’m going to stick to python, it’s easy to translate into other languages.

A Top Down approach is literally just that, we are going to start at the very top of this file and work our way down until we have successfully built our own implementation of an interpretor for this file format.

Now, Skyrim has an enormous amount of data they store in their save files, so we’re going to primarily be focusing on the header information. The same skills can be extrapolated and applied to the rest of the save file. You have probably realized at this point that this seems a daunting task, especially with the currently exposed information. The problem that you have as the audience is a lack of info. We need more information if we’re even going to come close to dissecting this, a classic scientific method, we need controls. So let’s get a few more save files, and have all the saves readily available off to the side in Skyrim to load at well with any hypothesis we wish to test.

TLDR Generalized Explicit Recap Thus far

- Take your current Save file and make a copy of it, put it in a save directory

- Do something in game, save again, make a copy of it, put it in a save directory

- Repeat n times (recommend ~5 to have a solid group of saves)

- Have the game open off to the side with all save games loadable.

To the Code

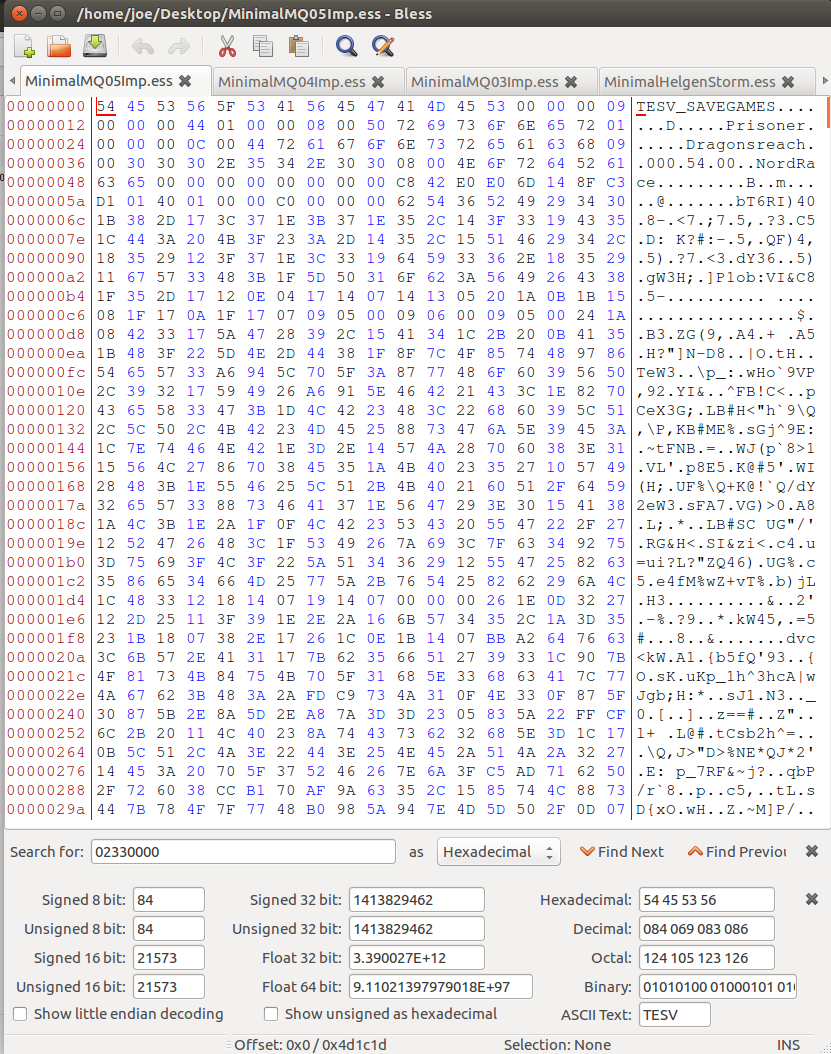

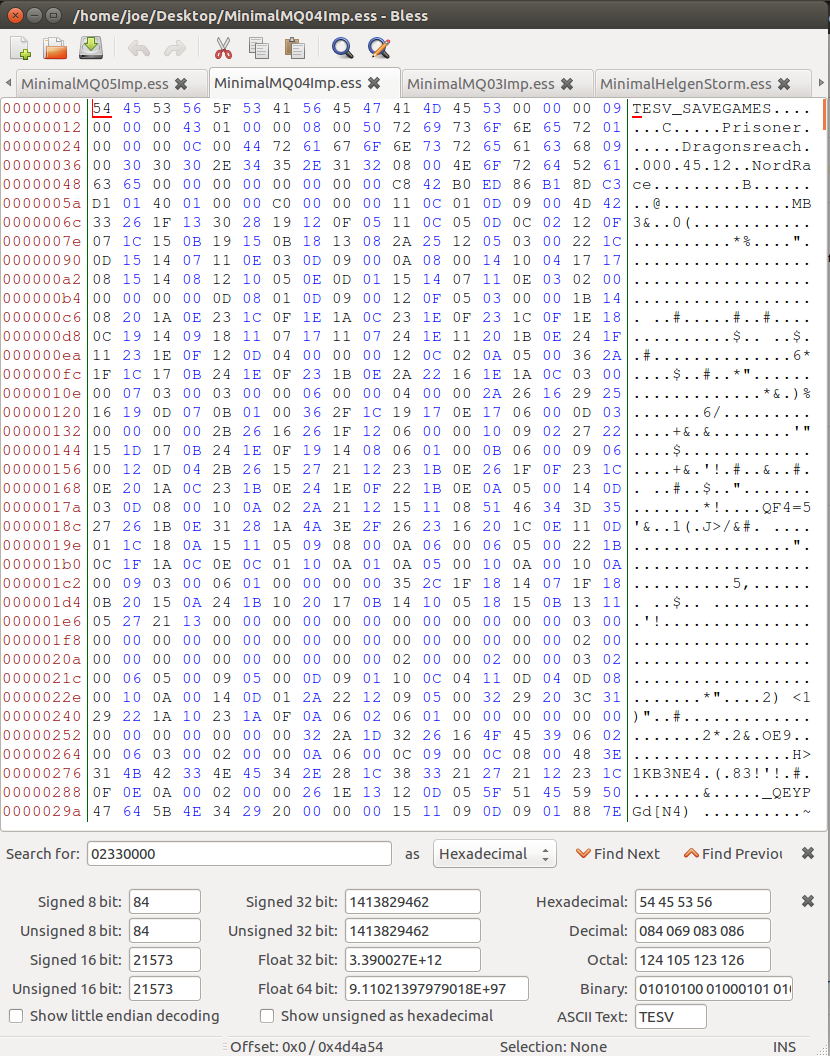

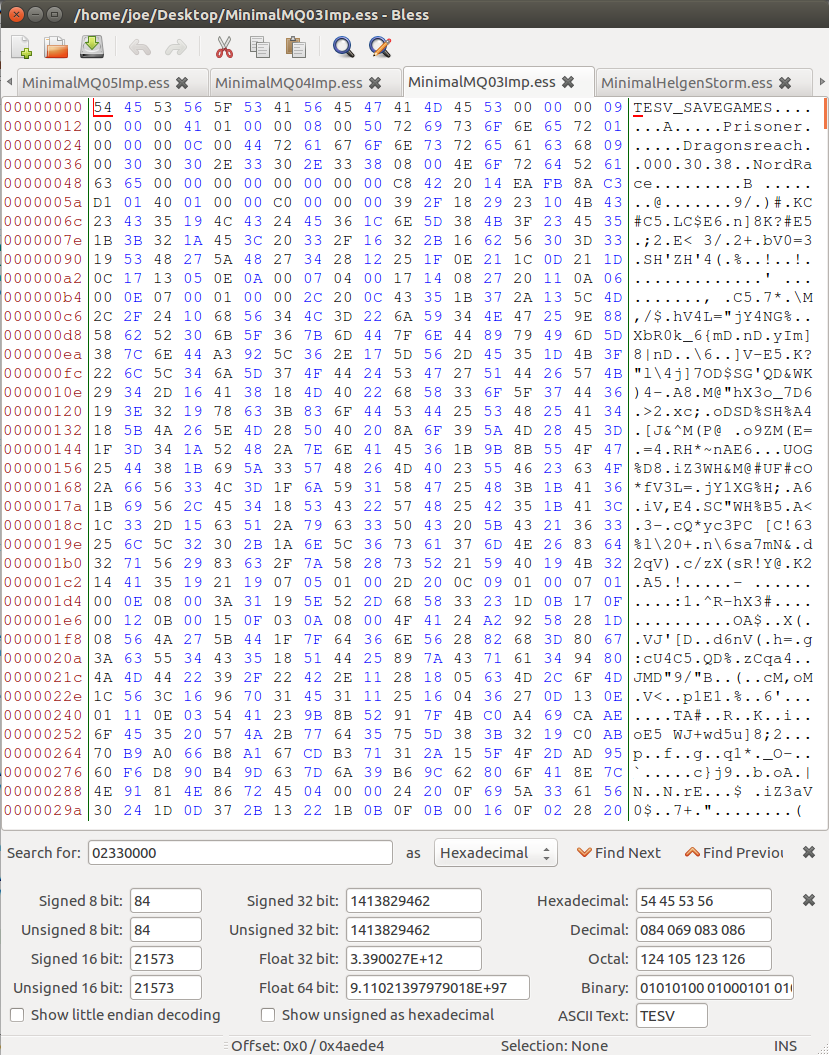

So now let’s get into the nitty-gritty details of our operation. We will be performing our topdown approach to the header of the Skyrim file. Observe the following files below:

We can immediately see a few commonalities between them, and that is our wonderful human brain at work that has been trained to identify patterns all of our life. Let’s start with the file MAGIC (file signature). This is a commonality that all developers ubiquitously present when they make a customized file format. It serves as a marker for the reader to identify the file with easy to verify that it is, indeed, able to be read. Our signature looks like 54 45 53 56 5F 53 41 56 45 47 41 4D 45 or in ASCII TESV_SAVEGAME. Let’s move over to our python script now that we’ve identified the first feature.

"""

TESV Save game file editor example (Top Down Approach)

:author Joe Bartelmo

:filename tesv.py

:version 3.6

"""

class TESVSaveGame():

"""

Wrapper to read and write our TESV Save game

"""

def __init__(self, filepath, open_immediately=False):

"""

Constructor for our file editor

"""

self.filepath = filepath

self.stream = None

self.opened = False

if open_immediately:

self.open_stream()

def __del__(self):

self.close_stream()

def close_stream(self):

"""

Closes the initialized stream

"""

if self.opened:

print('Closing Stream')

self.opened = False

self.stream.close()

def open_stream(self):

"""

Opens the initialized stream

"""

if not self.opened:

print('Opening Stream')

self.opened = True

self.stream = open(self.filepath, 'rb+')

self.assert_magic()

def assert_magic(self):

"""

Assert that the file signature is present

"""

self.stream.seek(0)

expected = "TESV_SAVEGAME"

actual = self.stream.read(13).decode('utf-8')

assert expected == actual, expected + " != " + actual

if __name__ == '__main__':

import sys

if len(sys.argv) != 2 and (len(sys.argv) != 3 or sys.argv[2] != '-d'):

print('usage: python testv.py <tesv_savegane> [-d]')

print('\t<tesv_savegame> location of skyrim savefile')

sys.exit()

TESVSaveGame(sys.argv[1], True)

So some advanced notes for development here: Never read in the whole file at once: parse the data, then write back. If anything we will read blocks of like-aligned data (eg: a zip file inside our file, or a checksum block). We do not read the whole file because it can be costly to our memory and there is no benefit from it because we are modifying this file anyway (generally). So our best bet is to keep a stream initialization open for the duration of our file.

Here we do not even bother with a getter because the magic is useless information, we included the assert_magic function strictly so we can see whether or not the file we have open is a valid file. Let’s move on in our file.

Continuation of Top Down

This next set of bytes is a little more tricky and require intuition. We have a byte that varies across all four files, however the remaining 3 bytes does not vary, they are constantly 00. Bringing back some of our knowledge on binary, usually 24bit integers are not common, we see denominations of powers of 2, 4 bytes being the most common (integer). We’re going to make the assumption that this is an integer. It varies across all files. In general we make the assumption that if there is an arbitrary set of 4 bytes that does not seem to have any reference, we assume it is either going to be one of the following:

| Type | How we make the assumption it is this type | General likelihood |

|---|---|---|

| length | The given set of 4 bytes does not have all 4 bytes allocated. Eg: 32 00 00 00 or 19 4b 00 00 Usually this length refers to the next set of bytes |

High |

| value | The given set of 4 bytes does not have all 4 bytes allocated. Eg: 32 00 00 00 or 19 4b 00 00. This can be very similar to a length type, so we identify a value by whether or not we are in a block, or if we know what type of data we’re observing. |

High |

| offset | The given set of 4 bytes has a high number that exists in the file as an offset, and looks like the start of a block of information Eg: 32 40 b0 00 where the offset 0xb4032 contains a distinguishable block |

Medium |

| checksum | The given set of 4 bytes appears random, does not link to anywhere in the file, and appears to have no relevance, but it changes frequently between files. Eg: 9b 14 aa 90 |

Low |

Based on the above we can safely assume that our value is of a length type. Let’s check to validate for each save game. All 4 are XX 00 00 00. This number means absolutely nothing to the notes I took of the important numbers and facts in my gamesaves. So I will make the assumption this is a length and not a value. In addition to my assumption, if we read the next 0xXX bytes of save games, our offset looks to always bee at a very large block of data. Our read data also contains (almost always) a set of 00 00 leading up to the block of garbled bytes.

File Structures

Before we continue, you need to understand the assumptions that I am about to make for the rest of this save file. Generalizations are very good when it comes to data analytics because it helps us more quickly identify how a structure is probably going to look once we tear it apart. In general, if a save file is binarily encoded, it will follow a typical file system structure.

Almost all file tables when it comes to storing simple information will follow this design pattern. There generally will always be 1) Versioning and metadata info 2) Data Table 3) Information that links from the datatable.

Coincidentally this is exactly how the Xbox 360 and windows operating systems also store their information. Microsoft loves their encapsulation. The Xbox 360 encapsulates all games in a container coined the Secure Transaction File System (STFS) which simply stores files within itself and maintains a hashtable which hashes blocks of the data from the save file for integrity. This was implemented so that designers did not have to worry about tampering, because they would have to get through the Xbox 360 file system before they even got to modify their gamesaves. To read more about how the 360 is structured you can go to free60.org.

Using File Structuring knowledge to our advantage

In what I’m now going to call our header metadata, we have a variable number of bytes. Let’s read our header data for a little bit and see if we can get the hang of this. Our next 4 bytes are static across all files 09 00 00 00. Using our assumption table above, I’m going to test to see if this is a length. It does not appear so because there is no link to anything, also it is static. Usually a length will not be static across 5 different save games. This is probably a value then. I have no idea what type of value it could be, but my assumption would be that this is versioning information because we are still in the metadata section of the file. Usually developer include versioning information in the top of their file systems. The next 4 bytes increments by one in each of my save files 32 00 00 00 33 00 00 00 … This is very clearly the save number of the game.

We now have a set of 2 bytes that are followed by an ASCII string (my character name) . It just so happens that these two bytes when converted to a uint16 is the exact length of my character’s name. This is a very common storage technique that C++ often uses for their string datatypes. We’re going to group this one into it’s own string category.

Updated Code with Current Extrapolated Information

Metadata reader:

"""

TESV Metadata

:author Joe Bartelmo

:filename tesv_header.py

:version 3.6

"""

import struct

class TESVHeaderMetadata():

"""

Analyzes and reads the TESV header metadata

"""

def __init__(self, stream, offset, length):

"""

All we need here is the stream and rely on the parent to open and close

"""

self.stream = stream

self.offset = offset

self.length = length

def get_unknown1(self):

"""

Seems to be a static integer, it's probably a version, it doesn't seem

to have any impact on the save game

"""

self.stream.seek(self.offset)

return struct.unpack('i', self.stream.read(4))

def get_save_num(self):

"""

Reads back the save number in the tesv file

"""

self.stream.seek(self.offset + 4)

return struct.unpack('i', self.stream.read(4))

def set_save_num(self, num):

"""

Sets the save number in the tesv file

"""

self.stream.seek(self.offset + 4)

self.stream.write(struct.pack('<I', int(num)))

def get_character_name(self):

"""

Gets the current character's name

"""

self.stream.seek(self.offset + 8)

size = struct.unpack('h', self.stream.read(2))

return self.stream.read(size).decode('utf-8')

# ...

Main Entry point:

"""

TESV Save game file editor example (Top Down Approach)

:author Joe Bartelmo

:filename tesv.py

:version 3.6

"""

from tesv_header import TESVHeaderMetadata

class TESVSaveGame():

"""

Wrapper to read and write our TESV Save game

"""

def __init__(self, filepath, open_immediately=False):

"""

Constructor for our file editor

"""

self.filepath = filepath

self.stream = None

self.opened = False

if open_immediately:

self.open_stream()

def __del__(self):

self.close_stream()

def close_stream(self):

"""

Closes the initialized stream

"""

if self.opened:

print('Closing Stream')

self.opened = False

self.stream.close()

def open_stream(self):

"""

Opens the initialized stream

"""

if not self.opened:

print('Opening Stream')

self.opened = True

self.stream = open(self.filepath, 'rb+')

self.assert_magic()

def assert_magic(self):

"""

Assert that the file signature is present

"""

self.stream.seek(0)

expected = "TESV_SAVEGAME"

actual = self.stream.read(13).decode('utf-8')

assert expected == actual, expected + " != " + actual

def get_header(self):

"""

returns meta data object

"""

self.seek(13)

header_size = struct.unpack('i', self.stream.read(4))

return TESVHeaderMetadata(stream=self.stream, \

offset=header_size, length=13)

if __name__ == '__main__':

import sys

if len(sys.argv) != 2 and (len(sys.argv) != 3 or sys.argv[2] != '-d'):

print('usage: python testv.py <tesv_savegane> [-d]')

print('\t<tesv_savegame> location of skyrim savefile')

sys.exit()

TESVSaveGame(sys.argv[1], True)

Moving on

By now I’m sure you get the point, this is a long an tedious process. The point of this article is to show you the proper software oriented approach, and not to do this entire save file. A team of us have already accomplished this for this exact save file. If you’d like you can practice and implement all of this information yourself with the data that has been previously established here. We are now going to briefly touch on different approaches to accomplish the same end goal. This usually is not the proper approach as we do not obtain the maximum information or properly discover the how the file system works inside the analyzed save game.

Alternative Approaches

In general, the above approach is how we map out an entire file without reverse engineering completely how the underlying game saves. This is sadly the fastest way to fully map out an entire save game. In general there are 2 more generalized approaches that I will mention: searching and decompiling.

Decompilation Approach

This is a little old school. When you think about it, all games are just a programs that sit on the hard drive. If we can go through and isolate the moment in time that the program saves in memory, we can analyze it and figure out which numbers align with what segment of the code. The problem with this approach is that it is messy and it would take longer than it would to simply produce a bunch of game saves, record data on a notepad and pencil, and do a little digging. If you however would like to learn more about this approach, I recommend taking a look at Boomerang for decompiling the executable to get the byte code locations. This may not be as fruitful however as an in-memory viewer where we can query information on the fly. My favourite application for this purpose is CheatEngine and for Linux scanmem. These will let you do queries in memory for your executable and even let you manipulate the current game in action (though for newer games you’ll probably just kill the executable).

I recommend using this approach on flash games, indie games, and any smaller game (in terms of executable size) that does not have memory scanners (See below)

Important Disclaimer:

Modifying the memory on the fly is often considered a type of malware attack, some antivirus programs will freak out when you attempt to use cheat engine or any other memory modification program. Additionally, a good deal of games have built in failsafes that detect when the memory is being modified, and have a reporting system to ban you. This is especially true for Steam who has a very well known VAC system to secure their games. This is another reason I tend to avoid this approach.

Searching Approach *

* most efficient approach in terms of time

This approach follows the same environment setup as the top down approach. We first obtain several gamesaves and record information about our save files just like our topdown approach and our decompilation approach. Now that we have our information we can search through the file and to find the offset of the target value to manipulate. Say for example in the given Skyrim file I wanted to modify my gold, and let’s say that I currently had 3302 gold. We have multiple ways that this gold could be represented in memory, so we’re going to use our Software Engineering reasoning to deduce that the value is going to be an unsigned integer (we can’t have negative gold, and the default max size for most values is 32 bits).

| Endian | Type | File 1 | File 2 | File 3 | File 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little | uint32 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Big | uint32 | 0x25663a | 0x25a342 | 0x2562bc, 0x422a4d | 0x25976b |

Above table is an offset chart linking where the gold was found in the file

The above is an example of a dynamic value, we couldn’t find a fixed position for the gold. But at least we found it! Let’s take a moment and perform the following steps:

1) Attempt changing the value and running the game 2) Record whether or not this process worked, if it did you’re good to go for the Coding Search Approach section 3) If not we need to figure out if this was a compressed block we just modified or if there is a checksum. Go to the Checksum Hunting section

Coding Search Approach

The naive approach would be to simply search for the value and modify it. The problem with this approach is that there could be duplicates (as seen by the above table under File 3). So there are two possible legitimate approaches. We can either isolate a static reference and compute the offset from the static offset, or we can fall back to the top-down approach. Although the top-down approach is the formal approach, if we are using the search approach we are in the interest of time, so let’s look for a static value around our gold (note that this approach will not formally work on the Skyrim because this found value isn’t actually the real gold value, it’s just an artifact that reflects the gold I have). The static artifact that is a commonality among all of the files is that this value is prefixed with 00 00 00 00 00 00 33 00 00 00 00 33 00 00 00 So we’re going to use this to find our target gold value. You can probably see already that this approach is fragile and will not always work.

Search Code

"""

TESV Save game file editor searching approach

:author Joe Bartelmo

:filename tesv_naive_search.py

:version 3.6

"""

from tesv_header import TESVHeaderMetadata

class TESVSaveGame():

"""

Wrapper to read and write our TESV Save game

"""

def __init__(self, filepath, open_immediately=False):

"""

Constructor for our file editor

"""

self.filepath = filepath

self.stream = None

self.opened = False

self.gold_offset = None

if open_immediately:

self.open_stream()

def __del__(self):

self.close_stream()

def close_stream(self):

"""

Closes the initialized stream

"""

if self.opened:

print('Closing Stream')

self.opened = False

self.stream.close()

def open_stream(self):

"""

Opens the initialized stream

"""

if not self.opened:

print('Opening Stream')

self.opened = True

self.stream = open(self.filepath, 'rb+')

self.assert_magic()

def find_gold(self):

"""

Determins the offset of the gold

"""

if self.gold_offset is not None:

self.stream.seek(0)

data = self.stream.read()

offset = data.find(b'\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x33\x00\x00\x00' + \

'\x00\x33\x00\x00\x00')

if offset == -1:

raise Exception('Could not find static initializer for gold')

self.gold_offset = offset + 15

def get_gold(self):

"""

Returns how much gold you have

"""

self.find_gold()

self.stream.seek(self.gold_offset)

return struct.unpack('i', self.stream.read(4))

def set_gold(self, amount):

"""

Assigns gold to a new value

"""

self.find_gold()

self.stream.seek(self.gold_offset)

self.stream.write(struct.pack('<I', int(num)))

if __name__ == '__main__':

import sys

if len(sys.argv) != 2 and (len(sys.argv) != 3 or sys.argv[2] != '-d'):

print('usage: python tesv_naive_search.py <tesv_savegane> [-d]')

print('\t<tesv_savegame> location of skyrim savefile')

sys.exit()

savegame = TESVSaveGame(sys.argv[1], True)

print(savegame.get_gold())

Checksum Hunting

If we think there is a checksum, this raises a few concerns. We have to figure out

1) What data is being hashed to produce the checksum 2) What type of checksum are we looking at

Deciding what Algorithm they used

Literally just bytesize, and then it’s a guess or check game. You can either write a small program to compute the hash over a block of data (for all hash types) and compare, or just use HxD’s built in checksum computer. Wikipedia has an excellent set of hashtypes and their digest sizes you can use to help you along here.

Deciding what data to hash

We need to understand that there are 2 types of developers, those that go through and try to secure their data (minority) and those that include a checksum because their boss told them. We assume the latter. Once we identify what may or may not be a checksum, we attempt to compute the checksum on all data, not including the checksum. For the latter approach, you brute force according to blocks that you’ve found to narrow your approach (eg header was 54 bytes, checksum comes after, i would try computing the header).